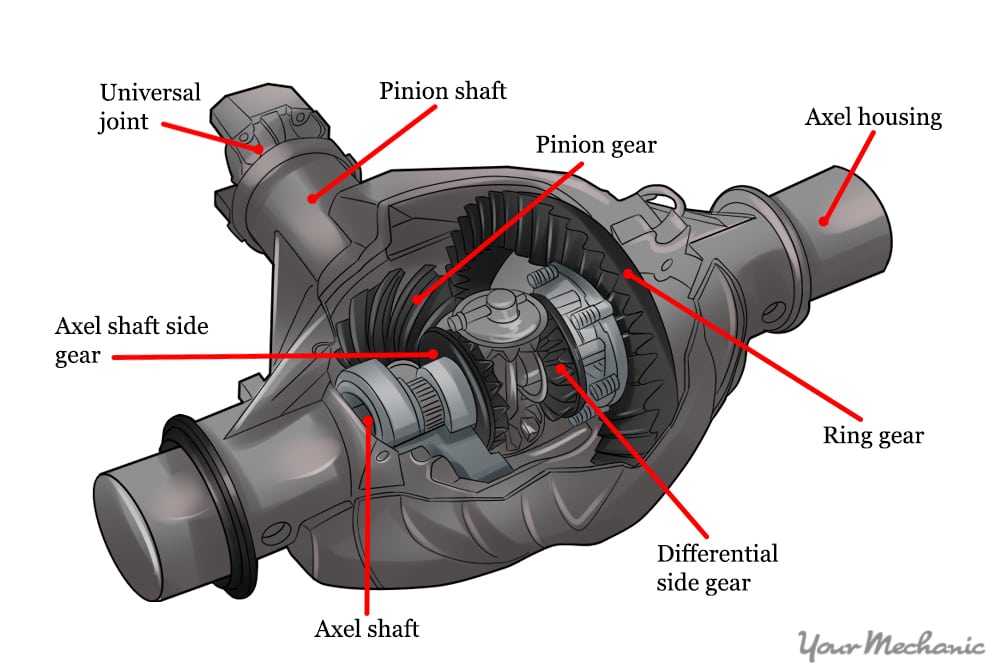

In automotive, references to a “differential” are common. Simply put, these are the gearing that move torque (power) from one point to another, usually by splitting it from one input source (the engine or transmission) into two outputs. For example, differentials are used to split the torque from the transmission and driveline to each wheel on an axle. They are also used to split power from the engine to each axle to create all-wheel drive.

Most differentials used in modern vehicles can split torque at different speeds. This allows, for example, one axle to receive more power than the other by default, but for that power split to change according to need. This is also what improves traction when one side of the car or one wheel on the car is not getting grip while others are.

Just about every vehicle on the road has a differential. Many have more than one. Rear-wheel driven vehicles have a differential on the rear axle, such as this Trac-Loc differential for Ford models. Knowing that, it’s also important to know that there are several differential types of differential in use.

Open Differential

This is one of the more common differential types in use. These are cheaper to make, easier to apply, and an open differential is pretty good at getting the basic job done. The idea behind it is to split power into two outputs at varying speeds for each.

The downside to the open differential is in its traction control. An open differential cannot “lock” power to a side and usually “free spins” on the side with the least amount of traction. This torque reduction to the wheel with a grip results in the slipping wheel spinning freely. Most vehicles compensate for this through their traction control systems by applying the brakes to the free-spinning wheel in order to force traction to the wheel with grip.

Locking Differential

This differential is almost identical to the open differential in terms of how it operates. The free spin can still happen in a locking differential, but can be overcome mechanically by “locking” the diff into a forced split. Most locking differentials lock at 50:50 with an even split of power distribution for each output. Some will split at a different, given set rate, but this is less common.

The locking differential is found on most off-road-ready vehicles like the Jeep Wrangler and is also found on many performance vehicles with an off-pavement bent, such as a Subaru STi. Some vehicles meant for towing performance may also have a locking differential to allow even distribution of power from axle-to-axle or wheel-to-wheel, but this is less common.

Limited-Slip Differential

The limited-slip diff works in a way similar to an open differential, but adds an automatic lock to prevent slipping (“free spin”). Most limited-slip differentials use a clutch pack, gear train angles, or fluid to accomplish the automated locking. Newer limited-slip differentials use electronically-controlled clutches to do it.

Mechanical-only limited-slip diffs are often slow to react to slippage, but are cheaper to make and give the driver some control over the timing for locking. The Eaton 19603 to the left is an example of a mechanical limited-slip diff. Some performance vehicles, such as the Mazda MX-5 Miata or the Toyota 86/Subaru BRZ will use a mechanical limited-slip differential (clutch in the Mazda, helical gears in the Toyobaru), for these reasons. Electronically-controlled limited-slip differentials are more commonly found in higher-end sports vehicles such as the BMW M3, Cadillac ATS-V, and some Ferrari models.

Torque-Vectoring Differential

Most common in serious performance machines, a torque-vectoring differential uses multiple gear trains to fine-tune the torque being delivered to each drive wheel. This allows changes in the amount of torque being delivered from one side of the vehicle to the other to improve performance in cornering and other maneuvers. For example, the moving gears in the differential can push power outward, slowing the turn of the inside wheel in a turn, which improves tire grip, allowing higher speeds through a turn.

Once limited only to track cars and race vehicles, the torque-vectoring differential is now often found in consumer performance machines like the Lexus RC F, Audi S4, and others.