An international team of researchers has uncovered the mechanisms of two families of software defeat devices for diesel engines: one used by the Volkswagen Group to pass emissions tests in the US and Europe, and a second found in Fiat Chrysler Automobiles. To carry out the analysis, the team developed new static analysis firmware forensics techniques necessary automatically to identify defeat devices and confirm their function.

After testing some 900 firmware images, the researchers were able to detect a potential defeat device in more than 400 firmware images spanning eight years. Both the Volkswagen and Fiat vehicles use the EDC17 diesel ECU manufactured by Bosch, the researchers noted. Using a combination of manual reverse engineering of binary firmware images and insights obtained from manufacturer technical documentation traded in the performance tuner community, the researchers identified the defeat devices used, how the devices inferred when the vehicle was under test, and how that inference was used to change engine behavior. “Notably,” the team wrote in a paper presented at the 38th IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy this week, “we find strong evidence that both defeat devices were created by Bosch and then enabled by Volkswagen and Fiat for their respective vehicles.”

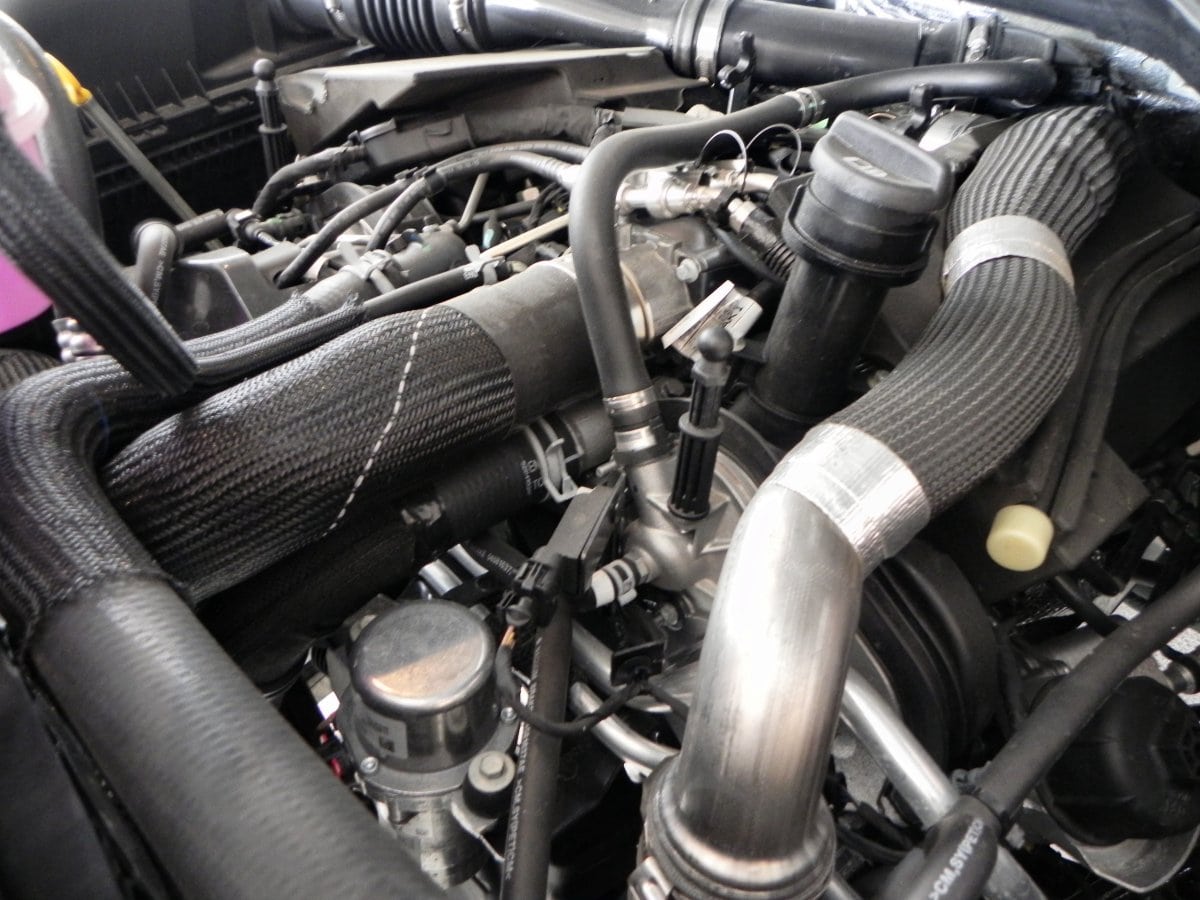

During current emissions standards tests, cars are placed on a chassis equipped with a dynamometer. The vehicle follows a precisely defined speed profile that tries to mimic real driving on an urban route with frequent stops. The conditions of the test are both standardized and public. This essentially makes it possible for manufacturers to intentionally alter the behavior of their vehicles during the test cycle. The code found in Volkswagen vehicles checks for a number of conditions associated with a driving test, such as distance, speed and even the position of the wheel. If the conditions are met, the code directs the onboard computer to activate emissions curbing mechanism when those conditions were met.

The team examined 900 versions of the code and found that 400 of those included information to circumvent emissions tests. A specific piece of code was labeled as the “acoustic condition”—ostensibly, a way to control the sound the engine makes. But in reality, the label became a euphemism for conditions occurring during an emissions test. The code allowed for as many as 10 different profiles for potential tests. When the computer determined the car was undergoing a test, it activated emissions-curbing systems, which reduced the amount of nitrogen oxide emitted.

Researchers found a less sophisticated circumventing ploy for the Fiat 500X. That car’s onboard computer simply allows its emissions-curbing system to run for the first 26 minutes and 40 seconds after the engine starts—roughly the duration of many emissions tests.