Although not technically a concept car, the Chrysler Airflow debuted in 1934 for a three-year production run and became one of the most influential cars ever built, despite its lack of commercial success. The focus on streamlining was very unusual for the time and the Airflow’s overall mixture of rounded aerodynamics and classic appeal still draw automotive lovers today.

Because of its influence and highly classic nature, the Chrysler Airflow deserves recognition here at Coffee and a Concept.

An Unusual Debut and Rocky Start

The Chrysler Airflow has the distinction of having had Orville Wright (yes, the flight pioneer) as part of its design team. The inception of the Airflow concept was with Chrysler engineer Carl Breer and his obsession with airflight and how form affects movement through environment. Legend attributes his idea to geese in flight, aircraft in military flight patterns, and to Breer’s interest in airships. The reality is probably all three of these things combined as they were all interests of his.

A publicity stunt was arranged by Chrysler in order to herald the coming debut of a very singular automobile. They drove an early version of the Airflow backwards around Detroit by reversing the axles and steering gear. This caused more panic than publicity, but the stunt got the car noticed, for good or ill.

The Airflow was then introduced in January of 1934 and began production later that same year. Production quality suffered, however, as the highly unusual design of the car radically changed what was the norm on a production line at the time, destroying the car’s reputation as the first couple of thousand on dealership floors were serious clunkers thanks to bad manufacture.

This was a torpedo in the Airflow’s otherwise stellar concept that destroyed the car’s chances of becoming mainstream.

The Design Begins

In the 1920s, automobiles were primarily of the “two box” design which came from simple carriage designs where the horses far out front were meant to pull the cart along, with the physics then creating a forward motion that counterbalanced the otherwise bumpy ride. In a horse-drawn carriage of balanced construction, this arrangement pitted the weight of the passengers against the trotting motion of the horses to create a smoother ride. In an automobile, where the engine is up close to the passengers, this put much of the weight on the rear axle and created horrible ride dynamics.

Further exacerbating this inefficiency were the squared off, simple designs of the vehicles of the era – little more than square farmer’s carts with (an occasional) roof over the top. Most featured wooden framework, extremely stiff springs, and very thin tires on tall wheels that offered no ride smoothing.

Improvements on these issues were slow in coming, though most automakers of the period were experimenting with ways to alleviate them. In Europe, for example, the first saloon designs were beginning to take shape to push the engine away from the passengers and create a more balanced ride while steel wheels of smaller diameter were appearing on both sides of the Atlantic.

Teaming with Orville Wright, Breer and fellow Chrysler engineers Fred Zeder and Owen Skelton began wind tunnel tests in a new wind tunnel (one of the first in automotive) built at Chrysler’s Highland Park site in Michigan. By 1930, they’d put more than fifty scale model forms into the tunnel to find better shapes for a car. Initially, which may have been what lead to the backwards-driving Airflow stunt, they found that current box-shaped automobiles were actually more aerodynamic in reverse.

At the same time, they began experimenting with unibody construction as a means of streamlining the shape to reduce drag from multiple joints. With a few experiments and a lot of design work, the team came up with the initial Airflow design, with its rounded, cascading grille and round-lensed, on-fender lighting, a low profile, and a “fast back” look to finish the initial concept.

Design of the Chrysler Airflow

Analyzing power-to-drag ratios, the engineers created a rounded hood, a lower profile, a split screen windscreen, and a continuous enclosed fender that followed through to the running boards and then to rounded rear fenders with full fender skirts around the wheels. Round rear view mirrors on thin stalks, slim door handles, steel wheels with full, smooth center caps, and the new, rigid body (thanks to the unibody design) created a striking appearance.

The unibody design also meant more safety and stiffness for better handling. The engine was pushed forward over the front axles and the passengers’ compartment was moved forward as well, so it sat completely in between the two axles rather than primarily over the rear.

This made the Chrysler Airflow one of the first true 50:50 weight distribution automobiles on the road, putting about 54 percent of the car’s total weight over the front axle, cantilevering to even out with passengers — a golden standard of weight distribution still used today.

This unibody construction with the weight slung between the axles rather than over them meant that Breer and his team had to re-think the suspension system as well. The total package meant that the car was one of the first all-steel builds (no wooden framework or “scaffolding”), sported larger seating, and had a better power-to-weight ratio and far more structural integrity than other cars of the time.

For its day, the Chrysler Airflow was one of the most innovative cars ever designed and showcased more modern improvements dictating things to come than almost any other vehicle of the era.

1934 Production Begins

When production on the new Airflow began, the factory planners were baffled by the design. The structure of the car required more welds than had ever been attempted by any Chrysler build before and the marketing department was unsure of what to do with the car within the tiny family of Chrysler autos.

The Airflow was ultimately sold under both the Chrysler and the DeSoto name, with the DeSoto Airflow being the only model offered under that sub-brand’s name. The Airflow sported a powerful flathead inline-8 cylinder engine in the car and a choice of two body styles: 2-door coupe and 4-door sedan. DeSoto and Chrysler models can be differentiated by their different grille, emblems, and differing instrument panels. A six-cylinder variant in the DeSoto line was offered and was also badged a Chrysler and sold in Canada in 1934, but dropped thereafter.

Several model types of the 1934 Airflow were offered by Chrysler, with most of the differences being in wheelbase length and interior trim level. As usual for the period, the “Imperial” moniker was used to denote the highest-status trim level. Only three original 1934 Chrysler Airflow Imperials are known to exist today.

Dismal sales, a smear campaign by General Motors, and consumers being skeptical of the Airflow’s looks meant that the DeSoto line sold almost not at all and the Chrysler offerings fared little better. Sluggish factory output and bad manufacturing in the beginning builds further destroyed the car’s credibility on the market.

In 1935, Chrysler changed some body styling to bring it back towards then-current tastes, largely destroying the Airflow’s aerodynamics in the process. A peaked grille, and a new “Airstream” model (which was nothing more than a standard car body of the day slightly rounded to appear vaguely similar to the Airflow) were also added. The Airstream sold well for the DeSoto nameplate.

In 1936, a trunk was added as the Airflow lost its “fast back” design and further shed its aerodynamic qualities. By 1937, the Airflow was sold only as one model (the Airflow Eight) and was further hammered into aero-undynamic submission for its final year.

In all, under 27,000 units of the Airflow were built in all of its various configurations. Only a handful of those were Imperial models. With the failure of the Airflow, innovation in design all but ceased at Chrysler until Virgil Exner appeared with fresh designs and partnerships with the Italian Ghia group in the post-war era.

Copycats in Japan?

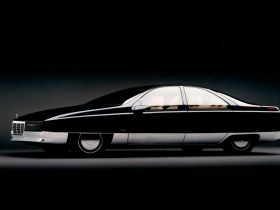

The pitiful sales figures for the car in the U.S. didn’t affect decisions at the fledgling Toyota company in Japan. With war drums beginning to rumble in Europe and a pending war with China, Japanese automakers weren’t shy about looking to the West for inspiration. Historians are conflicted over the actual inspiration for the Toyota AA of 1936 (pictured above). Other similar lines of inquiry and design in Europe, specifically Czechoslovakia with the Tatra T97, may have been more likely sources of inspiration for Toyota. Yet the AA is almost a direct copy of the Chrysler Airflow Imperial in appearance and build.

Photos herein and in the gallery courtesy of Wikimedia.